Join 1,394 other subscribers

UNRAVELING THE KNOT

ALLAN G. JOHNSON'S BLOG

Tag Archives: America

America’s Next Civil War

Posted by on Wednesday, February 8, 2017

I always thought there was only the one Civil War. The one grown men like to dress up and re-enact, the one about slavery.

Not to end slavery, but to decide something larger. Depending on how you hold it up to the light, the Civil War was a struggle between rival factions over what would become of the land still being taken from Native Americans, including the question of one nation or two. The expansion of slavery may have been the presenting issue—the one we’re taught about in school—and yet not be the point.

Which is to say, if it hadn’t been slavery, it would have been something else.

It wasn’t slavery, after all, that prompted our first civil war, our founding civil war, the war within the war known as the American Revolution, the struggle for liberty and independence that we celebrate on the 4th of July. The civil war that was fought between the rebels and the one-out-of-five colonists who were happy with the way things were and wanted no part of revolution.

The two sides made war on each other, eight long years of it, full of violence and destruction, by the end of which tens of thousands of British loyalists whose home this had been for generations, had lost everything and were forced to flee to Canada and beyond.

If you ask most people how many civil wars there have been, I’ll be surprised to hear them answer with more than one, which makes it important to note that this country was founded in no small part on the outcome of a war of neighbor against neighbor.

The second civil war was a continuation of the first even though the immediate cause was not the same. Because we were still fighting over what this land would be, and whose, and on what terms, and we have been fighting about that, in one way or another, ever since.

It is a struggle that comes of being a nation founded on conquered land where the victors and their descendants and beneficiaries neither originate nor belong. Not being indigenous, no one has an unimpeachable claim, and so the conquerors, having conquered, turn on one another in a perpetual struggle over primacy, turf, identity, and spoils. Not to mention latecomers hearing of a land of opportunity where they might get something for themselves.

It really doesn’t really matter to the essence of the thing how the sides are drawn—whether it’s unions and bosses or farmers and railroads or emancipated blacks and the KKK; or Catholics and Protestants, Christians and Muslims, immigrants and native born; reds and blues, real Americans and not; small town and big city, western rancher and suburban professional, more educated and less, the one percent or ten percent and everyone else.

It doesn’t matter because this nation’s defining struggle has been to get what you can get and then hold onto it. If you doubt this, go ahead and take all of that out of our history, and then consider what is left. No one would have come here in the first place, including the New England Puritans who practiced slavery on Native Americans and Africans almost from the beginning.

That struggle has been both enshrined and encoded as ‘freedom’ and ‘opportunity,’ which, of course, is not untrue. But there is also the underside that is something closer to pitched battles on union picket lines or the frantic headlong greed of the Oklahoma land rush of 1889. And greed and fear are never far apart. Just zoom in on their faces to see what I mean.

Because once you establish the idea that there is no such thing as enough, not to mention too much; that it’s okay to take what isn’t yours, or to convince yourself that it is when it’s not; or to profit from another’s misfortune; or that there is no higher virtue than looking out for yourself—then you create a world in which it is hard if not impossible to know whom to trust, or how far, for how long, or with what.

And so, the urge to civil strife is never far from erupting around one thing or another. Now it is the Trump Phenomenon and all the fault lines and conflict that it reveals. And an explosion of fear and anger that can make you wonder where it came from so suddenly, and out of nowhere, when, in fact, nowhere has always been right here, and it was only sudden for our not seeing how close it is all the time. It was waiting in the wings to go on, out back in the alley having a smoke, taking a break before the next act.

I believe that if you look closely, you will find that Americans have never liked or trusted one another very much, not if you ask them to look across the whole of who we are, coast to coast, north and south. You don’t have to go very far to feel as though you’re in another country, surrounded by a culture and a people you don’t recognize as your own.

Maybe it’s only me, but I doubt it. That we are only now, for example, coming to terms with the place of the Confederate flag in ‘American’ life, or whether this is a ‘white’ country or not, should tell you something about how deep the divisions lie, not to mention their longevity. And you can bet that when we think they are resolved, we won’t have seen the last of them.

Colin Woodard’s book, American Nations, describes not two nations in North America, but eleven, going all the way back to the first European invasions of one region or another. There is Yankeedom up north and the Left Coast and the Far West and El Norte in the southwest; Greater Appalachia, the Tidewater and the Deep South; the Midlands, New Netherlands, New France, the First Nations. Different stories, different ethnicities, different cultures, different methods and histories of conquest, subjugation, and exploitation, all with a bent to eyeing one another with suspicion from the start. Their boundaries rarely match state lines—Chicago, say, in Yankeedom, but the rest of Illinois divided between the Midlands and Greater Appalachia. And if you compare that map with red and blue counties in this last election, it explains a lot. It can give you chills.

We have never been one nation, under God or otherwise, so it’s no surprise that the idea of civil war may come so easily to mind.

In the runup to the last election, it was not uncommon to hear Trump supporters say that if Clinton were elected, there would be civil war. Not all hell breaking lose, or protest, lawsuits, and strikes. No, civil war. They could use the words knowing they would resonate, and confident they would not be greeted with ridicule or disbelief. Because this has happened here before. It is something we know how to do. There are monuments and testimonials. It is in the make-up of this place and who we are as a result. And if we imagine that we are beyond all that, we are wrong.

Clinton, of course, did not win, but that is beside the point. The election was the deep rumble of one tectonic plate straining against another. And of all the warning signs, the one that stands out the most, the precursor and necessary condition of every civil war, is not the level of anger and fear, or the most heavily armed citizenry in the world. It is a profound ignorance of one another and ourselves, matched by an equally profound and sometimes boastful lack of curiosity.

It is all the times I have heard someone express amazement that anyone could vote for____, and then the exasperated, I just don’t understand those people! And I want to say that if you cannot understand how the world might appear in a way that would make such a choice seem reasonable, compelling, and obvious, or how your own choice could appear to be just as inexplicable to someone else, then you’re being too easy on yourself. Try harder.

But instead of listening for an answer, instead of imagining how the world could be seen, and how we are seen as others, we pathologize and demonize ‘those people’ by explaining their behavior as a simple matter of who they are.

We transform them in our minds into our own imagined inability to understand. They become the inexplicable, beyond thought and feeling and empathy, the stranger, the strange, the estranged, the not me, the not us, the monster.

Take your pick of any civil war, foreign or domestic, past or present, and see if it doesn’t sound a lot like that. All you need is someone to fire the first shot.

Listening is a skill, a discipline. It must be cultivated and practiced. It does not come naturally or easily, especially in a culture saturated with social media that encourage the voicing of opinion without having to know much at all, not to mention listen to or even be aware of other human beings. That tells us that one opinion is as good as any other, and so what do I need with you and yours?

If I tell you what I am for or against, what I believe is true about this or that, in the end you will have a mountain of information that is no different from what you can hear in one place or another. And you will have no real idea of who I am.

Because opinions are too easy, and too readily confused with thought.

When I teach about difficult subjects such as gender and race, I often begin the term by telling the class that I am not interested in their opinions (gasp). We all have them. It’s like showing me what’s in your pockets or your bag, what you brought for lunch. That’s nice, but I don’t really care.

What does interest me is how you think, how you got to that opinion, that point of view, how it’s connected to what else you think about, or have known, how one thing informs or reinforces or contradicts another, how you put together this reality you live inside.

For that to happen, I have to listen. I have to turn myself over to understanding you more than affirming or justifying myself. I must be willing to temporarily lose myself, as if what you have to say is all that matters in this moment, because, in fact, it is, because you are the one who knows what I do not, which is you.

I ask them questions—Why? being my favorite—to clarify or connect one thing to another. But, otherwise, it is not about me. Or, for that matter, about them, but a way for all of us to deepen our understanding of what it is to be a human being in this strange place called America.

But we cannot do this if we are too afraid, as fear destroys curiosity, or if we care only about being right. But I repeat myself.

Maybe this is where we are. And maybe it is too late to pull back from the brink. Maybe it always was. I don’t know, of course. But this seems to be a crossroads we’re standing at, as we have so many times before, a decision we are called upon to make.

And one more opportunity to find out who we are, and what we are prepared to do, and for what.

___________________________

For related posts, see:

“Idiots, Morons, Lunatics, and Fools: When Worldviews Collide”

“History Does Not Repeat Itself”

“What Are We Afraid of?”

For a recent history of the American Revolution, see Alan Taylor, American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804. W. W. Norton, 2016.

Colin Woodard, American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America. Penguin, 2012.

For a history of slavery in the colonies, see Wendy Warren, New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America. Liveright, 2016.

America, Love It or Leave It

Posted by on Friday, September 5, 2014

[Given the length of this post, it is divided into three parts. To go to Part 2, click here. For Part 3, click here.]

Part One

Yesterday I saw a bumper sticker showing an American flag and the words, “Proud to Be American.” It reminded me of a conversation I had many years ago with a young German during which I mentioned how much it meant to me to be American. I will not forget the look on her face, puzzlement and chagrin, as she told me she felt nothing like that about her country, and never had.

I thought, well, of course, given what Germany had done, the Holocaust, the war. I had read about young people struggling with the history they inherited from their grandparents and parents, how it weighs on them, the legacy of being German.

In the years since, I have recalled that conversation with a growing awareness of my own country’s legacy—millions of Africans having their lives taken from them in the Middle Passage and across generations of enslavement, Jim Crow, lynching; the betrayal, ethnic cleansing, and genocide of Native Americans; the brutal subjugation of Filipinos resisting the expanding American empire after the Spanish-American War. And, of course, there is Vietnam, and it remains to be seen how Iraq will be remembered.

For myself and many other Americans, it is impossible to miss that our history includes things that today would be called crimes against humanity. These are not things that can be shrugged off as mistakes or flaws in national character as in, ‘nobody’s perfect.’ Such horror is the stuff of what many Germans struggle with to understand what it means to be German given what was done long before they were born.

It is a struggle not only for the young, but the country as a whole. Go to Berlin and you will find a prominent monument to the Holocaust and the massive failure of the German nation and its people. It is not without controversy, but, still, there it is, and controversy means they have to talk about what to make of the past and what it means for the present.

It makes sense that Germany would build such a memorial, which will exist long after the people who lived what was done are gone, and generations of their descendants. And yet, in Washington, D.C., where I was born, there has never been a national commemoration, much less a monument, to the millions of Africans who lost their lives in the building of the American empire. There is no memorial to the Native Americans from whom the continent was taken under threat of extermination. There is a monument to the 58,000 Americans who died in Vietnam, but nothing for the millions of Vietnamese caught in what became an American war, directed by Americans in pursuit of American aims.

We have no annual day of reflection and atonement, no honoring the memory of all those dead, the countless ruined lives. As far as I can tell, there has never been such a day.

I am wanting to understand the difference of memory between her country and mine. Germany remembers, I imagine, because they lost the war and had no choice. There was the Allied occupation and then Nuremberg and the films and the history and the worldwide hunt for Nazi war criminals. There was no escaping what they had done because the world knew and had the power to hold them to account.

But America has never been subordinated to a power that could compel its people to look at what was done and answer for it. Perhaps that is the difference, and yet there must be more to memory and accountability than whether someone makes you do it.

There is also the act of choosing to remember, to hold ourselves to account, of which there is barely a trace in the mainstream collective ‘we’ that speaks with authority on the national stage, the cultural voice that represents ‘America’ to itself and the world through public displays, stories, high school history books, monuments, and rituals. As an American, I feel both a need and an obligation to understand why.

Part Two

I woke up this morning to the memory of another bumper sticker, this one from the late 1960s, part of the backlash against the anti-Vietnam War movement

I have often wondered about that message, both the ‘America’ that we’re supposed to love or leave and the prominent role of ‘leaving’ in the American story.

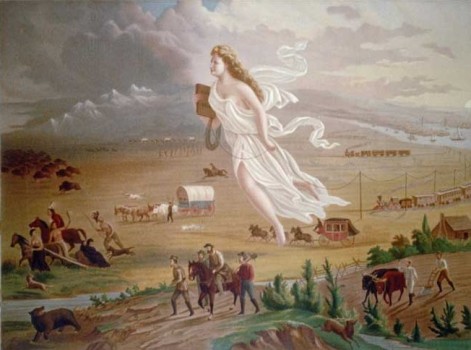

Some version of ‘If you don’t like it here, go somewhere else,’ is embedded in our national psyche. Almost from the first settlements there were people striking out on their own, and when waves of immigrants came in the 1800s, western territories were seen as a way to relieve the pressure of population and poverty. Go west! the newcomers were told, and they did, by the millions, the leading edge of America’s Manifest Destiny to conquer ‘inferior races.’ (On the left side of John Gast’s famous 1872 painting below, note the buffalo and Native Americans being driven into the darkness by the advance of ‘white civilization’.)

In the following century, the Great Depression drove migrants west from the Dust Bowl in search of something better, only to be told to keep moving until they found a place where no one else wanted to be. And there was the massive black migration to the urban north and today’s return-migration south.

On a smaller scale, after the election of George W. Bush, there were stories of people being so upset they were planning a move to Canada.

Go back far enough, and leaving one place for somewhere else is a big part of who we are and what we came from. It seems a strange thing for a people to have in common and out of which to make a nation, a sense of rootless wandering in pursuit of a new and more promising life, everyone for themselves, getting what you can while you have the chance and then hanging on to it.

Norman Rockwell notwithstanding, I have rarely if ever heard ‘the American Dream’ referred to as anything else. Certainly not as the answer to some yearning to be part of a unified people, a community, a meaningful way of life, a culture that offers a sense of value and belonging, the fulfillment of a need to be home. Most people did not pack up and leave the country of their ancestors in search of that. They didn’t just get tired of being Norwegian or Italian and decide they’d rather be American.

No, the American Dream’s defining core, what it does not exist without, is the achievement of material success through competition, without restraint and without having to depend on or answer to anyone else.  The result is an America that is not so much the home of a true and unified people as it is the setting, the arena, where the competition and striving for success take place.

The result is an America that is not so much the home of a true and unified people as it is the setting, the arena, where the competition and striving for success take place.

But isn’t such freedom what America is all about? Isn’t that the essence of the American Dream? I think it is, but not in the way that we’ve been taught.

Freedom is important to the Dream primarily because it makes possible the unrestrained pursuit of it without our being accountable to others. Freedom itself is not the point of the Dream, but a precondition. After all, the moment we are here, we are already free, and as such, it is not a ‘dream’ to be pursued. And this freedom is not merely the freedom to, but the freedom from—from having to belong to something larger that might limit what we do. Strangely, then, the American version of freedom includes not being tethered to a country that is accountable for its own history, to be present but unaccountable and therefore unattached.

But attachment and accountability lie at the heart of what I think my German friend was trying to express that day—her responsibility as a German for things she did not do, held to account for what her country had done in the past, her country as it is now being inseparable from what it once was. And this is no less true for anyone who would claim that country as their own, who would feel the right to say, “I am German.” Or American.

To question why someone would feel accountable for things they have not done apparently does not occur to her, but it does come up routinely among Americans who disavow a connection to this or that troublesome part of our history.

How unlike that is from the family story where the parents die and the children discover that all that’s been left to them is a mountain of debt. The moment of truth comes when they must decide whether to pay it off even though they are not required to and benefited from what was borrowed, whether to assume the obligation on behalf of the family itself.

Who or what, I wonder, is claimed and honored by such a choice? And what does it say that they would feel this way not only about their parents as individual people but ‘the family’ and its honor as something larger than themselves?

What then does it mean to have such feelings about one’s country? And what does it mean to not?

Not only do we refuse responsibility, but any suggestion of accountability for what America has done is routinely dismissed as outrageous and ridiculous. To be accountable implies a power beyond ourselves great enough to hold us to account, and most Americans are having none of that.

On top of which is the argument that it isn’t fair to be held responsible for something we did not do. But this confuses the ‘we’ that is a group of individuals with the collective ‘we’ that is a nation or a people. If ‘America’ is not the sum of what was done—its history right up to this moment—then what is it? What else is there? Without that, what is there to belong to or feel proud of, to love or, for that matter, to leave?

And what does it mean to call ourselves ‘American’ if we get to pick and choose which part of that history to claim as our own? Are we responsible only for the America we like, that makes us feel good and proud? Is there a statute of limitations on being claimed by the bad things but no limit on our claiming the good? Are we responsible for what our nation has done only in the last five minutes? The past week? A year? A decade? As far as we, personally, can remember? Or only if we did it ourselves?

And if we are not responsible for things we did not do, then why do we get to feel good—not to mention proud—about things we also did not do?

There is a deep split about the America we are supposed to either love or leave. It feels just a little schizophrenic, and makes me wonder what kind of love that would be.

Part Three

If my friend does not feel good about being German, if there is sadness and grief, guilt and shame, even anger when she thinks of it, does this mean she does not love her country? Who or what is it that needs to be loved, and what does it mean to love it? And if we do not, what then?

To love is to attend to the well-being of another. In loving you, I attend to you and what you need, and to know that, I must know and accept the reality of who you are. That requires still more attending, which, over time, binds me to you and you to me. Our mutual well-being becomes second-nature, inseparable from who we are.

It is easy to love someone we do not know, who seems attractive and delightful, who pleases and reflects well on us. That’s why falling in love can be so tricky, based more on romantic ideas about someone than who they really are.

Harder still is to love someone who displeases or does horrible things that make us want to turn away. I think about the parents of people who commit some brutal crime, and I wonder what form does love take in the face of that. What does it mean to say, “I love you,” then? Who is it that I love? The child I remember, the boy with the sweet smile and the tender heart? But not this one, who caused such pain and loss? How do I separate the two inside myself? Is it even possible? And at what cost?

To be torn in this way, I would have to feel bound to another in a way that feels part of who I am. My children will always be my children, no matter what they do or, for that matter, what I do. It isn’t up to me or them. If it is good, then a blessing, and, if not, something to be reconciled or endured, bound by love to one another for better or for worse.

As far as I can tell, the mainstream of this country, including leaders of all kinds, does not feel this kind of bond with the thing we call ‘America,’ unable or unwilling to reconcile the good and bad of what it is and what it came from. It’s like adopting a dog from the pound and imagining her life begins now, with us, that she brings no troubled history that will become not only part of our lives but also our responsibility. But the truth is that her past is with us every minute of the day, because we have ‘adopted’ not just a dog, but an entire history, a life, that happened before we came along.

In denying this about America, we cultivate a bizarre state of unconditional love for an idea of it—inspiring stories of heroic figures, flags waving, bands playing, lofty speeches about how wonderful ‘we’ are. We thumb our national nose at the rest of the world and gaze at our national self in a mirror that hides every flaw, like those fashion models made to appear so perfectly ‘beautiful’ that they don’t look like any human being you ever saw. Much of the world, having seen what we can do, both good and bad, knows better, but we tell ourselves (and them) that it doesn’t matter what they think, because they are not American.

I realize now that some of what I saw in my friend’s face was not just how she felt about her country. There was also her puzzlement that I could have no such feelings to struggle with myself.

What is it that needs to be loved and what does it mean to love it?

Poor America—sliced, diced, and disfigured to make only the good parts show, all those claims to your success while your failures are left to fend for themselves, orphaned and disowned

I wasn’t born yet

My ancestors did not own slaves

They weren’t even here

The Republicans did that

It was the Democrats

We had good intentions

We were trying to spread democracy

It was for their own good

They’re envious, ungrateful

We had no choice

That isn’t how it happened

They did it, too

A long time ago

Get over it, move on

It never happened at all

I wonder what we are so afraid of that we would work so hard to live so far removed from reality. And what would happen if we allowed ourselves, out in the open, together, to see America whole. How bad would it be. What would we lose. What would we gain. And how much less dangerous would we be to ourselves and the rest of the world.

Alexis de Toqueville, traveling through America in the early 1800s, observed that the new nation might pose a special danger to others because its citizens were so proud of their democracy and had such a high opinion of themselves as a result, they might not see their own capacity to do terrible things to those they would judge to be inferior.

With the advantage of historical hindsight, I would add that our high opinion of ourselves also encourages us to pick and choose the good parts from the rest. And blinds us to how the national past lives on into the present in the suffering and injustice inflicted on Native Americans, blacks, and other peoples of color both here and around the world. And how ready we are to bomb and invade other countries in the name of protecting ‘American interests’ and promoting the ‘American Way.’

There is no monument in Washington to the millions of innocent Iraqis who have died in the bloody war our country set in motion. Or to those being killed by U.S. drones over Afghanistan and Pakistan.

I wonder, then, how do we love an America that includes all that? What would it mean and what would it require of us?

It occurs to me that a clue might be found in how we routinely speak of America, not as a thing, but as a living being—

My country, ‘tis of thee . . . I sing

Stand beside her and guide her

God shed His grace on thee

—which makes me ask why not love America as we want to be loved ourselves, whole and real. Who, after all, wants to be loved as someone they are not? Who wants to be loved based on a lie?

And then it comes to me that, of course, to love America is to love ourselves as American, since America is not alive, not conscious, not aware of whether ‘America’ is loved or not and how. In the end, this really is about us, the ones who call ourselves American, inseparable from the legacy passed down from the generations of Americans who went before.

It is about how we live America, because that is what decides what America is and what it will be.

After centuries of disavowing our own history, finding a way to love America as something whole and real is a daunting task. There are limits to taking responsibility after so much time and I do not pretend to know what those limits are or how we go about it except to make the question a part of our lives, to speak it out loud and invite others to the conversation, however hard that may be. Throughout our history many Americans have struggled with the question of how to both love America and see it as it really is, a work that must continue because our future depends upon it and finding out is part of what we are called to do.

That it will be hard and disturbing and frightening is no reason not to do it. We are citizens, after all, and this is what citizens do. It is part of our service to the nation. It is common to hear people sing the praises of the military, how brave they are, how grateful we are for the risks they have taken on behalf of their country. On behalf of us. But the vast majority of people in this country have never done any kind of national service. We pay taxes and vote every two and four years and that is all. We do nothing in service to America that might actually interfere with our lives or put ourselves at risk, even the risk of feeling bad or in doubt or afraid.

Finally, at long last, together, as a nation, after so many generations of denial, how do we not find a way to step up to this?

And, if we do not, will we not have left after all?

_____________________

If you liked this post, you might want to read “National Disobedience Day.”